Schilderijen

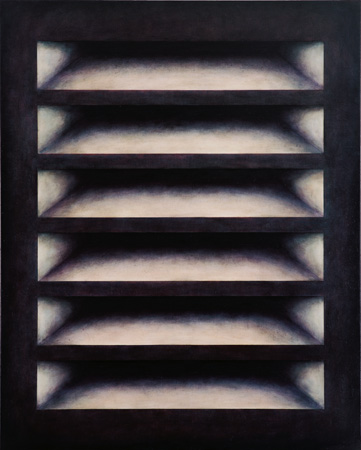

Tatort (No. 01-05), 2002-2004

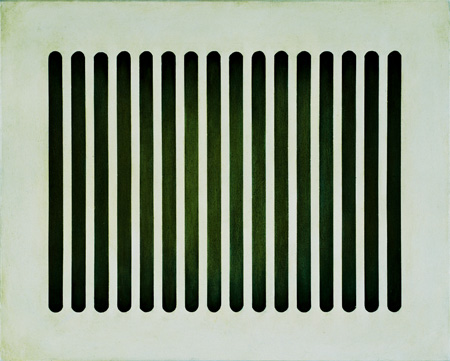

Grids (No. 01-12), 1999-2005

Babs Bakels’ paintings (2000-2005):

Grids and spaces between life and death

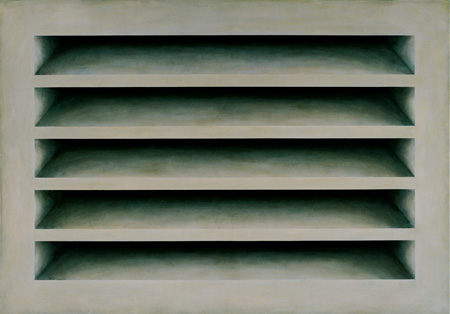

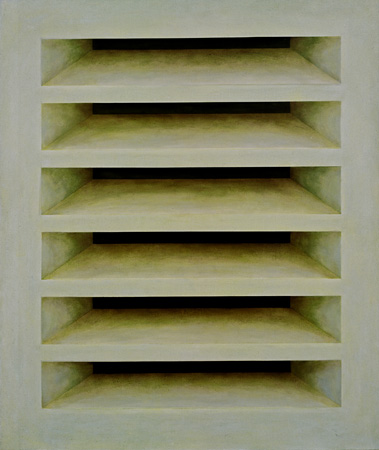

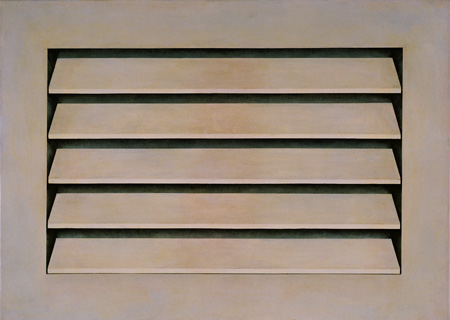

Margriet SchavemakerIn 2000 Babs Bakels (1971) started in her Amsterdam studio on a series of paintings called ‘grids’. Apart from a few smaller studies, most canvases are large sized, such as Grid no.8, which measures 1,80 by 1,45 m. Seen from a distance, the paintings appear as abstract geometrical patterns, but on closer inspection they turn out to be near photorealistic reproductions of all possible types of grids (deep grids with small rectangular openings, shallow grids having horizontal openings with round corners, etc.) Each painting is made up of a limited, undefined colour spectrum. It is as if a lens of an undefinable colour has been placed before the camera. Bakels achieves this unreal effect by means of the traditional method of glazing. Glazing was a particularly popular technique in the Renaissance and was used by the Flemish Primitives and by Italian masters like Piero della Francesca. By applying numerous layers of transparent paint, the paintings acquire a translucent, polished surface. Bakels also mixes a small amount of colour through each layer of glaze, thus creating an unusual colour spectrum which causes each grid to fluctuate between realism and an abstract, dreamlike composition.

As such, Grids is an interesting step in the use of grids in modern art history. In the previous century, artists from Piet Mondriaan to Agnes Martin attempted to banish illusionism from painting by applying endless series of geometrical patterns and grids. These grids accentuated the power of the two-dimensional form and broke with the traditional view that the art of painting offered a window on the world. By turning the abstractions into representations of grids, Bakels has reintroduced realism. Yet it is a moderate realism, as the abstract grids of her modernistic predecessors continue to echo in her own paintings, especially when her paintings are seen from a distance. Moreover, the quality of three-dimensionality is confined to the shape of the grids: the chinks in the grids do not offer a view of a world beyond. It is a deliberate strategy, because in this series Bakels is mainly interested in grids as a means of blocking out another world. For Bakels there is a world we cannot know behind the Grids, which is death’s unknown world. We want to take a look but we are unable to. It remains the world on the other side until our time has come.

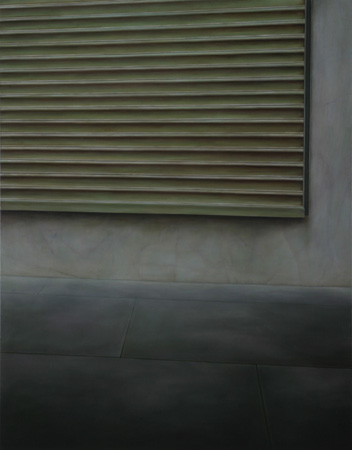

In 2002 Bakels decided to visualize the world behind the grids. In some of the paintings bleak spaces are visible through the chinks where people have succumbed to acts of violence. Soon the grids were omitted and Bakels shows the murder scenes without the protective filter of the grid. The basis for this series of paintings, entitled Tatort (crime scene) are quick photo shots of murder victims, made by police officers recording the details of the crime scene for further investigation. Bakels took these photographs from newspapers, books and the Internet. Her main interest is in the composition of these readymades: the proportions of the walls and the floor surfaces, the cut-outs and the perspectives are adapted en bloc but the aspect of human suffering is avoided. The spaces are cleared of any stains of blood and are transformed by Bakels into sterile, aesthetic compositions.

Bakels’ style of painting reinforces the absence of the human element because her hand is hardly discernible. The scenes on the canvases are the total opposite of the expressionistic brush technique by which artists express their deepest emotions. Bakels does not work in a fit of inspiration: her artistry is very rational, controlled, and layer after layer she manages to erode any trace of herself. The result is a series of emotionless, almost mechanically produced paintings on the basis of unpolished photographs. The terrible scenes forming the subject matter of the photographs and the paintings are filtered away by Bakels in two ways: in terms of contents and in terms of painting technique. In the Tatortseries, the artist has transformed herself into the grid that was the subject of the earlier Gridsseries.

The theme of the Tatort series is closely related to the ‘guilty landscapes’ which the Dutch painter Armando but also Anselm Kiefer chose as subjects, whereby landscapes or spaces are turned into silent witnesses to horrendous crimes. But there is yet another layer of meaning, as Bakels in the Tatort series resists the documentary photography dominating the World Press Photo and especially more recent art exhibitions like Documenta XI in Kassel. The rapid click with which the camera records and then aestheticizes the anguish of people, their pain and poverty, gives way to an excessive slowness in Bakels’ paintings, as each layer of glaze must dry well before the next one can be applied, a process which can take months. The suffering of the victims is also filtered away. And yet the Tatort paintings are not simply void. Firstly, the victim’s fate is commemorated by the title, so that the viewer is invited to project a relevant image onto the spaces. Secondly, because of their sheer dimensions, the viewer as it were becomes absorbed, is sucked into the spaces on the canvases. Instead of observing death (as is the case in documentary photography) the living viewer assumes the place of the deceased. In this way Bakels dissociates herself from the voyeurism which characterizes modern culture, offering instead a conceptual game and an almost physical experience between life and death.

The paintings which the Amsterdam artist Babs Bakels has been quietly producing over the past years prove that the ancient themes of life and death can still produce absorbing images. At the moment she is working on a series of sculptures in which she makes use of ‘dead alive’ material (bones, hair, nails etc.), and a photography project involving residents of homes for the elderly in Osdorp, in West Amsterdam, whereby she records their life stories and living spaces before and after their deaths. It is to be hoped, however, that Bakels will not abandon painting altogether. Her search for the least personal expression in the highly personal medium of painting is a source of enduring fascination, which, combined with the superb quality of her work, is something one rarely encounters.

Amsterdam, January 2005